- Joined

- Dec 6, 2010

- Messages

- 33,422

- Reaction score

- 5,683

In Shock, Perth Western Australia 1 of the driest city's, we don't catch any water from storm water drains, it runs straight into the ocean

Well, the good news is Perth officials learned all they can about water recycling from our Groundwater Replenishment System in Orange County and brought the technology home to replenish your underground aquifers. It should be operational now, I think.

While our facility's production rate is ramping up to the tune of 100,000,000 gallons per day, which makes it the biggest water recycling system in the world, the pompous bitches in LA insists on calling water recycling "toilet to tap" and steadfastly refuses their city's effort to adopt the technology, even though the recycled water is considered to be ultra-pure, and they would rather continue stealing from other people's lakes and rivers instead.

---

Nation’s Largest Water Recycling Plant Expanding in Orange County

By David Gorn December 14, 2016

By David Gorn December 14, 2016

California’s prolonged and ongoing drought has at least one positive outcome. It has prompted water officials across the state to quickly develop new sources of water — and one of those new sources is flushed water.

The Orange County Water District is leading the nation in wastewater treatment to replenish groundwater supplies — and that project is expanding now, designed to eventually supply water to 2.4 million people, about 40 percent of all water needed in Orange County.

The success in turning used water into drinking water in Orange County is being copied across the state, according to David Sedlak, a professor at UC Berkeley and co-director of the Berkeley Water Center, which monitors the state’s water policy and progress.

“Water agencies in California have been watching Orange County for years now,” Sedlak said.

The state has set aside $1 billion for water recycling, including treating wastewater to drinking water standards. The Santa Clara Water Authority and San Jose consulted with Orange County officials, and they’re now leading the way in Northern California. A huge “toilet-to-tap” effort is being planned by the city of Los Angeles, which could eventually top Orange County’s output.

Almost every water district in the state is planning some kind of wastewater-to-drinking-water effort now, Sedlak said, and that kind of rapid progress is unprecedented.

“When you think about the normal glacial pace with which water infrastructure projects usually get built,” he said, “things are moving at a lightning pace in California.”

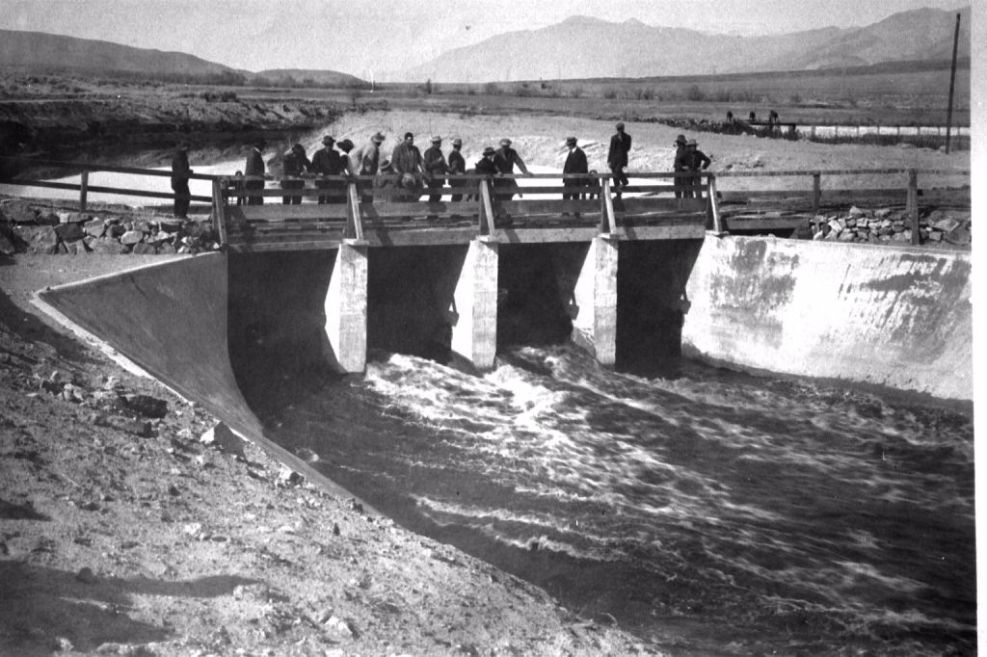

Nowhere quicker than Orange County, which currently processes 100 million gallons of wastewater a day. When the expansion is completed in 2022, that number is expected to climb to 130 million gallons a day. The district uses reverse osmosis and filtering technology to exceed state standards for drinking water, and then it pumps that water underground to refill its groundwater basin and aquifers.

That additional underground step accomplishes a number of things. By refilling the groundwater basin, there is less danger of the subsidence problem afflicting the Central Valley, where groundwater pumping has caused the land to sink as much as 2 inches a month. Filling the aquifers also keeps saltwater intrusion from the ocean away from freshwater supplies.

And pumping it back underground might filter the water even more, and help keep the famous “ick factor” out of the conversation.

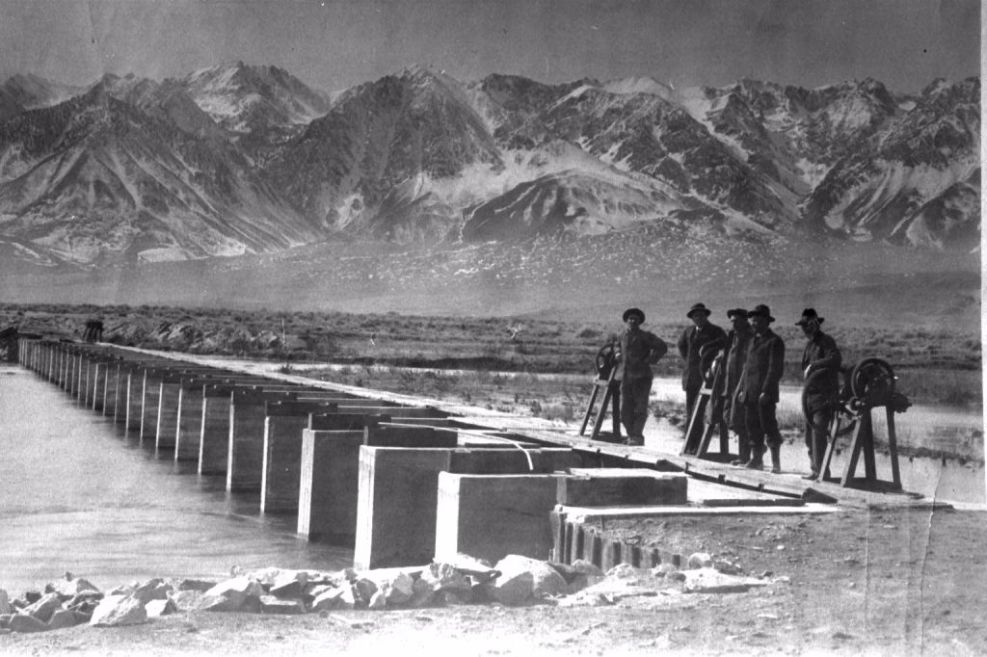

Water flows into Anaheim Lake, where it will be recharged into the Orange County Groundwater Basin.

In Orange County, all water flushed by residents will eventually become drinking water. And that’s in the cards for much of the rest of California, said UCLA water policy researcher Madelyn Glickfeld.

“It’s going so quickly,” she said. “I think pretty soon all of the water we have in sewer treatment plants is going to be recycled.”

Obviously, water officials have been prodded by the drought, now entering year number six in California. Recent rains have eased some of the problems for northernmost areas, but federal officials (NOAA) estimate 87 percent of the state is still in drought, with over half in severe drought.

The state cut water allocations again this year. This time districts are getting 20 percent of contracted water, which is better than last year’s 10 percent allocation but still much less than most districts need. Glickfeld said districts don’t want to rely on that water.

“At the Water Replenishment District of Southern California, their goal is to stop importing water,” Glickfeld said. “And they think they can.”

https://ww2.kqed.org/news/2016/12/1...r-recycling-plant-expanding-in-orange-county/

Last edited: