- Joined

- Dec 6, 2010

- Messages

- 33,424

- Reaction score

- 5,686

OxyContin maker’s settlement plan divides victims of opioid crisis. Now it’s up to the Supreme Court

WASHINGTON (AP) — The agreement by the maker of OxyContin to settle thousands of lawsuits over the harm done by opioids could help combat the overdose epidemic that the painkiller helped spark. But that does not mean all the victims are satisfied.

In exchange for giving up ownership of drug manufacturer Purdue Pharma and for contributing up to $6 billion to fight the crisis, members of the wealthy Sackler family would be exempt from any civil lawsuits. At the same time, they could potentially keep billions of dollars from their profits on OxyContin sales.

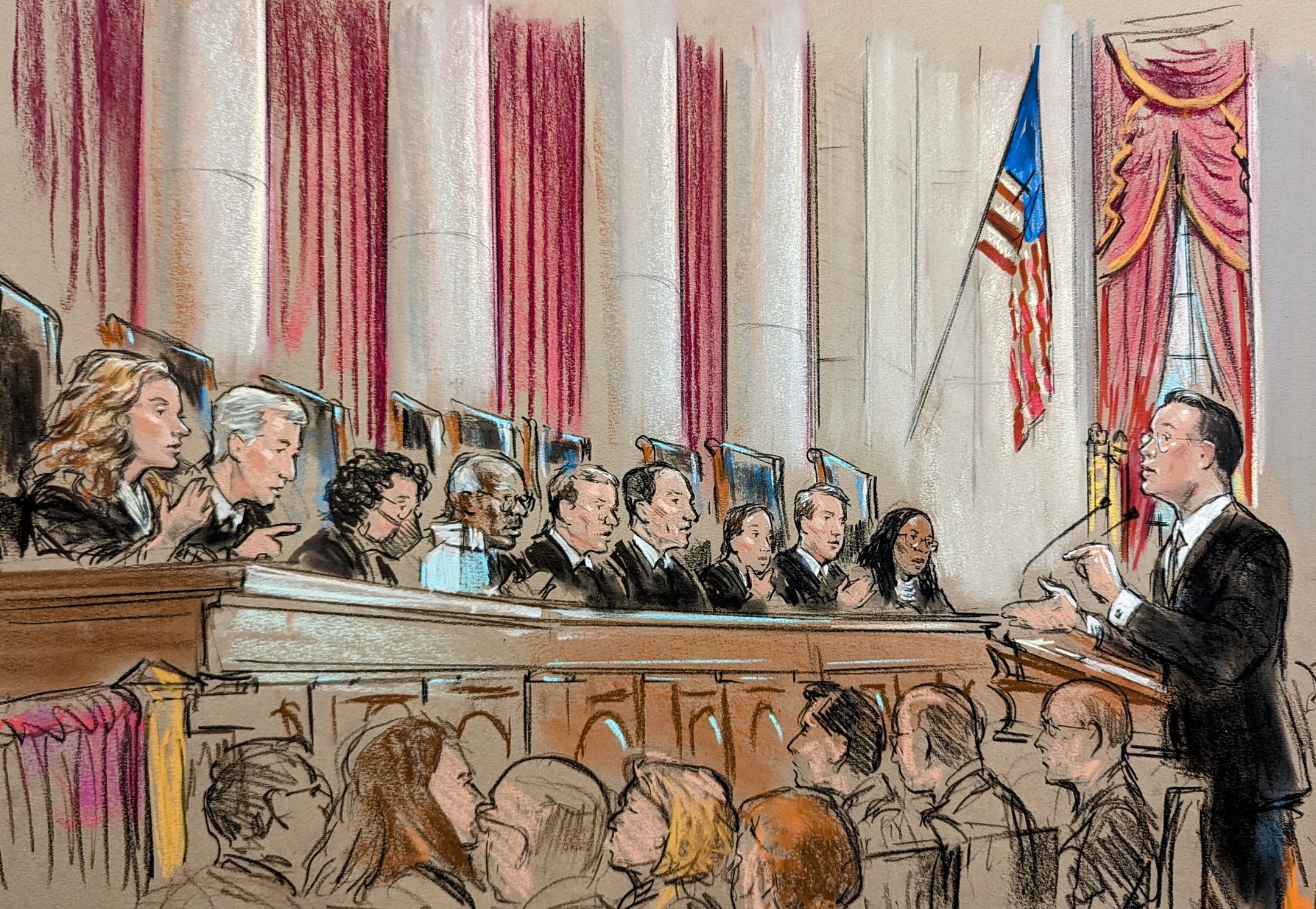

The Supreme Court is set to hear arguments Dec. 4 over whether the agreement, part of the resolution of Purdue Pharma’s bankruptcy, violates federal law.

The issue for the justices is whether the legal shield that bankruptcy provides can be extended to people such as the Sacklers, who have not declared bankruptcy themselves. The legal question has resulted in conflicting lower court decisions. It also has implications for other major product liability lawsuits settled through the bankruptcy system.

But the agreement, even with billions of dollars set aside for opioid abatement and treatment programs, also poses a moral conundrum that has divided people who lost loved ones or lost years of their own lives to opioids.

Ellen Isaacs’ 33-year-old son, Ryan Wroblewski, died in Florida in 2018, about 17 years after he was first prescribed OxyContin for a back injury. When she first heard about a potential settlement that would include some money for people like her, she signed up. But she has changed her mind.

Money might not bring closure, she said. And by allowing the deal, it could lead to more problems.

“Anybody in the future would be able to do the exact same thing that the Sacklers are now able to do,” she said in an interview.

Her lawyer, Mike Quinn, put it this way in a court filing: “The Sackler releases are special protection for billionaires.”

Lynn Wencus, of Wrentham, Massachusetts, also lost a 33-year-old son, Jeff, to overdose in 2017.

She initially opposed the deal with Purdue Pharma but has come around. Even though she does not expect a payout, she wants the settlement to be finalized in hopes it would help her stop thinking about Purdue Pharma and Sackler family members, whom she blames for the opioid crisis.

“I feel like I can’t really move on while this is all hanging out in the court,” Wencus said.

Purdue Pharma’s aggressive marketing of OxyContin, a powerful prescription painkiller that hit the market in 1996, is often cited as a catalyst of a nationwide opioid epidemic, persuading doctors to prescribe painkillers with less regard for addiction dangers.

The company pleaded guilty to misbranding the drug in 2007 and paid more than $600 million in fines and penalties.

The drug and the Stamford, Connecticut-based company became synonymous with the crisis, even though the majority of pills being prescribed and used were generic drugs. Opioid-related overdose deaths have continued to climb, hitting 80,000 in recent years. That’s partly because people with substance abuse disorder found pills harder to get and turned to heroin and, more recently, fentanyl, an even more potent synthetic opioid.

Drug companies, wholesalers and pharmacies have agreed to pay a total of more than $50 billion to settle lawsuits filed by state, local and Native American tribal governments and others that claimed the companies’ marketing, sales and monitoring practices spurred the epidemic. The Purdue Pharma settlement would be among the largest. It’s also one of only two so far with provisions for victims of the crisis to be compensated directly, with payouts from a $750 million pool expected to range from about $3,500 to $48,000.

Lawyers for more than 60,000 victims who support the settlement called it “a watershed moment in the opioid crisis,” while recognizing that “no amount of money could fully compensate” victims for the damage caused by the misleading marketing of OxyContin.

In the fallout, parts of the Sackler family story has been told in multiple books and documentaries and in fictionalized versions in the streaming series “Dopesick” and “Painkiller.”

Museums and universities around the world have removed the family’s name from galleries and buildings.

Family members have remained mostly out of the public eye, and they have stepped off the board of their company and have not received payouts from it since before the company entered bankruptcy. But in the decade before that, they were paid more than $10 billion, about half of which family members said went to pay taxes.

Some testified in a 2021 bankruptcy hearing, telling a judge that the family would not contribute to the proposed legal settlement without being shielded from lawsuits.

Two family members appeared by video and one listened by audio to a 2022 court hearing in which more than two dozen people impacted by opioids told their stories publicly. One told them: “You poisoned our lives and had the audacity to blame us for dying.”

Purdue Pharma reached the deal with the governments suing it — including with some states that initially rejected the plan.

But the U.S. Bankruptcy Trustee, an arm of the Justice Department responsible for promoting the integrity of the bankruptcy system, has objected to the legal protections for Sackler family members. Attorney General Merrick Garland also has criticized the plan.

The opposition marked an about-face for the Justice Department, which supported the settlement during the presidency of Donald Trump, a Republican. The department and Purdue Pharma forged a plea bargain in a criminal and civil case. The deal included $8.3 billion in penalties and forfeitures, but the company would pay the federal government only $225 million so long as it executed the settlement plan.

A federal trial court judge in 2021 ruled the settlement should not be allowed. This year, a federal appeals panel ruled the other way in a unanimous decision in which one judge still expressed major concerns about the deal. The Supreme Court quickly agreed to take the case, at the urging of the administration of President Joe Biden, a Democrat.

Purdue Pharma’s is not the first bankruptcy to include this sort of third-party release, even when not everyone in the case agrees to it. It was specifically allowed by Congress in 1994 for asbestos cases.

They have been used elsewhere, too, including in settlements of sexual abuse claims against the Boy Scouts of America, where groups like regional Boy Scout councils and churches that sponsor troops helped pay, and against Catholic dioceses, where parishes and schools contributed cash.

Proponents of Purdue Pharma’s settlement plan often assert that federal law does not prohibit third-party releases and that they can be necessary to create a settlement that parties will agree to.

“Third-party releases are a recurring feature of bankruptcy practice,” lawyers for one branch of the Sackler family said in a court filing, “and not because anyone is trying to do the released third parties a favor.”

OxyContin maker's settlement plan divides victims of opioid crisis. Now it's up to the Supreme Court

The legality of an agreement by the maker of OxyContin to settle thousands of lawsuits over the harm done by opioids is going before the Supreme Court.

Last edited: